A legal anomaly meant that the Church of St Charles, King

and Martyr in the village of Peak Forest could issue its own marriage licences,

free of the rules of the Established Church – and parental consent.

Peak Forest came into being in the early 1500s, when an

enclosed park for the King’s deer was created between Tideswell and

Chapel-en-le-Frith. A house, known as ‘The Chamber of the Forest’, was built

for the park steward, and became the administrative nub of the newly forming

village. St Charles, King and Martyr was built in 1657 by Christiana, Countess

of Devonshire, and, as it stood on land belonging to the Royal Forest, lay outside

the jurisdiction of the Church. Its vicar – officially, and rather wonderfully,

called the Principal Officer and Judge in Spiritualities in the Peculiar Court

of Peak Forest – could perform marriages at any time, for people who did not

necessarily reside in the parish, without having to read the banns first.

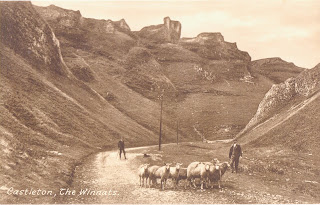

One of the Peak District’s most intriguing tales concerns a

couple who, in 1758, were eloping to Peak Forest. Clara and Allan had made it

as far as Castleton, when they stopped at a local inn. Later, as they rode

through lonely Winnat’s Pass, they were robbed and murdered by a group of men

who had also been in the pub and noticed

the money-bag they were carrying. The lovers’ bodies were never found

but divine justice was theirs: of their five assailants one broke his neck

(also in the Winnat’s Pass), a second was crushed by falling stones, the third

committed suicide and the fourth died mad; the fifth died young, making a

death-bed confession to the crime.

Clara’s red leather saddle was recovered and can still be

seen in the shop at Speedwell Cavern. It is said the ghosts of the couple haunt

Winnat’s Pass to this day.

For another 50 or so years after Clara and Allan made their

ill-fated bid to marry, couples headed to Peak Forest for a ‘foreign marriage’ to

be performed. But in 1804 an Act of Parliament brought St Charles, King and

Martyr into line with the rest of the Church of England. The register notes: ‘Here endeth the list of

persons who came from different parishes in England and were married at Peak

Forest. This was a great privelege for the Minister, but being productive of

bad consequences, was put an end to by an Act of Parliament.’

And so ended one of the most romantic traditions of the Peak.

The original St Charles, King and Martyr was demolished in 1876 when

the 7th Duke of Devonshire decided to replace it with the present building,

which stands about 20 yards from the old site. Stone from the first church was,

however, used in the construction of new reading rooms in the village, so at

least something of its spirit remains.

St Charles, King and Martyr; photo by Poliphilo

Winnat's Pass, early 20th century

.JPG)