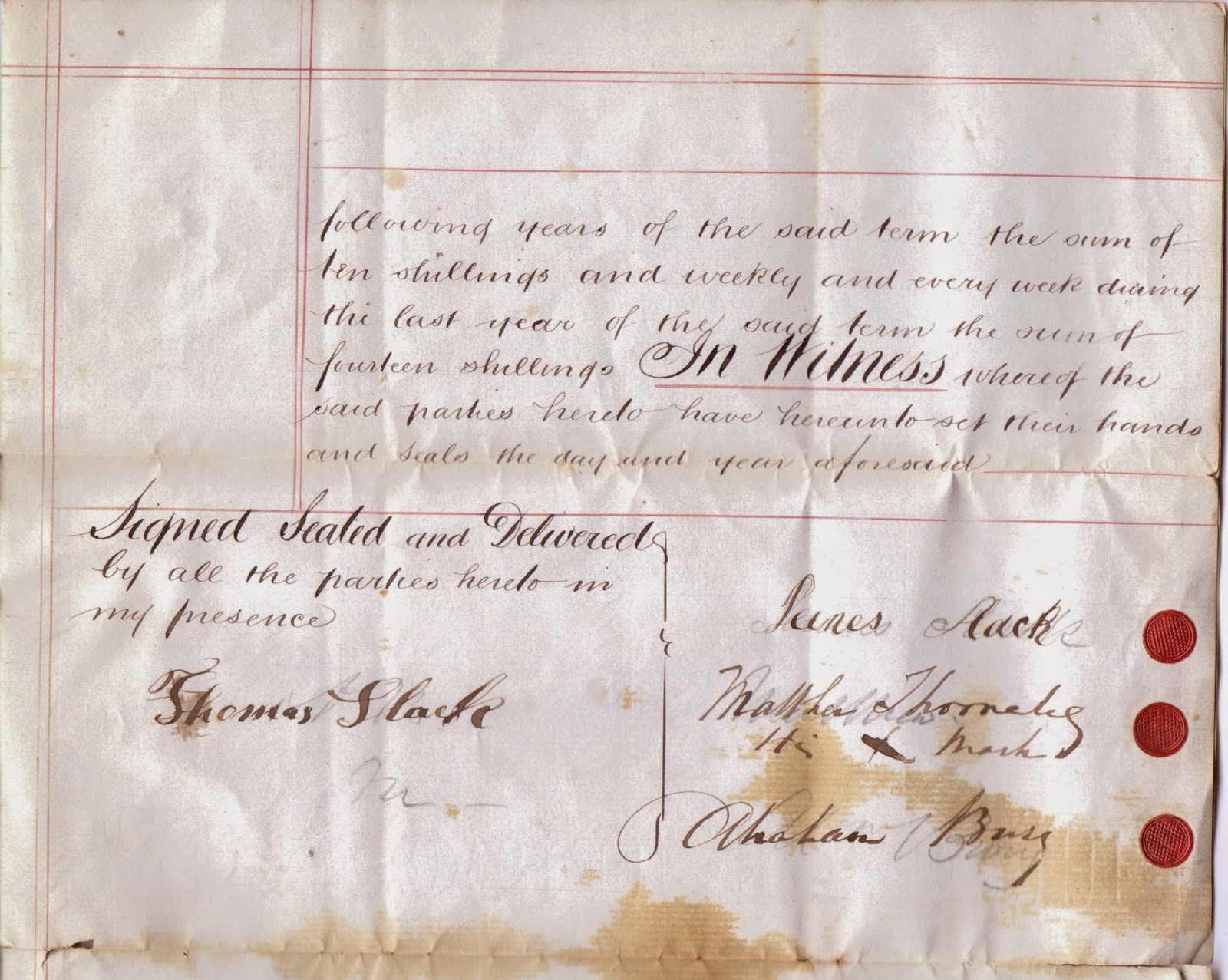

By making his mark at the bottom of this indenture 16-year-old

Matthew Thornley of Sutton, near Macclesfield took the first step in what he

hoped would be a successful career, becoming apprentice to one Abraham Bury,

earthen- and blackware manufacturer.

By making his mark at the bottom of this indenture 16-year-old

Matthew Thornley of Sutton, near Macclesfield took the first step in what he

hoped would be a successful career, becoming apprentice to one Abraham Bury,

earthen- and blackware manufacturer.

The deal was struck in February 1867 between Matthew and his

father, beer house keeper James Slack, on the one part and Abraham on the other.

Under the agreement Matthew and James swear that, until Matthew reaches the age

of 21, he will:

his said master faithfully serve, …. his said master’s secrets keep,

his lawful commands duly obey and execute … he shall do no damage to his said

master nor suffer it to be done by others but to his power shall and will

prevent the same … the goods of his said master he shall not waste, embezzle or

destroy nor give or lend the same to any person or persons …. Neither shall he

absent himself from the service of his master during all or any part of the

said term without his said master’s consent. But in all things and upon all

occasions shall and will behave and demean himself as a good and honest

apprentice ought.

As well as this James promised to find and provide ‘good and

sufficient meat, drink and lodgings and appropriate clothing of all sorts’ for

Matthew, as well as ‘washing and medicine in case of sickness’, for the full

term of the apprenticeship.

In return for all this Abraham pledged to ‘well and truly teach

and instruct … the apprentice in the art and trade or business of an

Earthenware Manufacturer and thrower of Earthen or Blackware’. He would pay

Matthew ‘the sum of eight shillings weekly and every week’ for a year, and then

ten shillings a week until the final year of the apprenticeship, when Matthew

could look forward to fourteen shillings a week - about £30 today.

Before all this, the 1861 census shows that Matthew was living

with his parents, James and Ann Slack on Byron’s Lane in Sutton. Again, James is given

as a beer house keeper (the local would be the King’s Head but this isn’t

stated), and Matthew is shown as a labourer at a silk works. He’s living with siblings

James, Martha and William Thornley and Thomas and Mary Slack; so presumably

this was Ann’s second marriage.

Matthew’s change of career came courtesey of one of his

neighbours: Abraham Bury operated from premises further down Byron’s Lane, and

was best known for tile and brick-making. A successful businessman, he became

Mayor of Macclesfield in 1870-71, dying in 1873.

Matthew seems to have done well with his apprenticeship and he

stayed in the trade. Come the 1881 census he is working as a potter, supporting

a wife and two children on Old Mill Lane.